“After a period of consistent monitoring and prompt punishment [they] began to regulate their own behaviour.”

What is being described here? Interestingly, my own instinctive answer was “children”. It is, in fact, prisoners. These words are from French philosopher, Michel Foucault’s, analysis of power and carceration. He was describing the concept of the panopticon, a form of prison inspired by the experiences of eighteenth and nineteenth century social reformer Jeremy Bentham when he stayed with his brother Samuel in Russia.

Born in 1748, only one of his seven siblings survived their early years. This was, at the time, an all too familiar but still personally devastating experience. Focused on the idea of “happiness as an absence of pain” and believing that actions which promote the maximum amount of happiness should be pursued, he helped to develop the concept of utilitarianism. He was in favour of legalising homosexuality as well as the idea of universal suffrage. He only took up law to please his father and loathed it. As a critic of social systems, he got into prison reform ideas and developed the idea of the panopticon as an efficient way to increase productivity and manage behaviour within the prison population. Having spent almost all of his modest fortune and absolutely all of his reputation on the idea he gave it up.

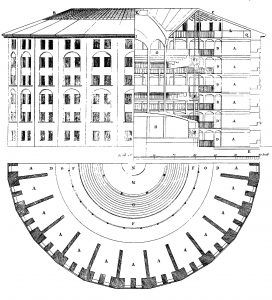

The sketches by Bentham below illustrate his idea. A central figure, who cannot be seen, is in the middle of a round of back-lit cells where the inmates lie in a perpetual state of possibly being seen.

This design and the thinking and commentary it has inspired bear, for me, startling resemblances to early childhood experiences.

A child is also watched and their behaviour is judged. Seen from all around by a parent who can be seen but is not understood (not until a baby reaches 4-5 months do they recognise a care-giver as separate from themselves). And, like the prisoner, the baby/child can see but not judge the care-giver. It’s not able to for many years, in fact, and, even when it can, it’s often not safe to do so. The parent sees and judges, decides what is good and bad – usually swiftly, often with no explanation and, sometimes, with violence. The child’s sense of trust in the external world, as well as their sense of trust in themselves, is moulded by how adequately the external world responds to their needs and validates and explicates their feelings.

“Childhood entails a type of enslavement from which one cannot escape” – Neil Smelser, sociologist

Children, like the inmates of the imagined panopticon, quickly learn that their behaviour generates consequences and this, in turn, when repeated over time, dictates their future actions. These modifications are often understood, within the context of psychology and attachment theory, as adaptive mechanisms. The child learns, through cause and effect, that certain behaviour brings reward or punishment, or an inconsistent mix of both. The baby, and younger child, needs care and seeks approval and so adapts to the environment in which they find themselves.

The home can be a haven or a place haunted by the spectres of trauma. For most of us it is both (see also: adolescence and trauma and c-ptsd). Much of what happens to us as children is unsettling and frightening: the sheer volume of new experiences, as well as the emotional and physical changes, are unique in the life-cycle. There are many theorists who believe childhood to be the most dangerous time of our lives and yet society is invested, perhaps because of this, in creating an impression of it as an idyll. There’s a lot of talk about “the best years of our lives” and yet we do not listen to, or question/doubt anyone who talks of the harms caused during this “golden” time. Social and cultural denial of childhood trauma is very real as writer Alice Miller found when she published her controversial, yet influential and perceptive, work on childhood in 1979.

As with the weather, there’s a big difference between the thunder of traumatic individual experiences and the clammy fog of a trauma-inducing environment. Many people will talk of happy childhoods and have no recollections of any particular “incidents” and yet there is pain, addiction, poor relationships with people, work or food and drink in adulthood. These factors are telling a very different story.

When the atmosphere of the home is dominated by the invisible gas of anxiety or alcoholism, we breathe it in unaware of how much it’s limiting us now, and in the future. The child grows up knowing what fresh air tastes and smells like, failing to recognise it and often preferring what is familiar. The atmosphere of adult life often mirrors the atmosphere of childhood: the anxiety and anger we experienced may not be flashes of lightening that flare up clearly when recalled in the mind but are, instead, a fog, leaving us feeling lost and, all too often, at a loss as to why.

When the atmosphere of the home is dominated by the invisible gas of anxiety or alcoholism, we breathe it in unaware of how much it’s limiting us now, and in the future.

In their ground breaking book Recovery, Herbert Gravitz and Julie Bowden say that nearly half of all adult children of alcoholics don’t recognise their parent as an alcoholic when they leave home. The authors also identify a common feeling that, on hearing about it, made many things clear to me: the sense of things not being right, of not feeling “well” but not knowing why. This internal disconnect can also mean many people minimise or invalidate their own feelings and consider that they are over-reacting or being silly. All too many families will readily agree that the now-adult just needs to meet the right guy/girl, get the right job or stop eating / drinking / smoking etc… Society reinforces this by legitimising only certain forms of trauma (when they legitimise any at all!) and/or denying the severity and frequency of the problem.

These traumas are inter-generational. They have been handed down to us through, and by, our families and care-givers and, if they’re not seen and understood, are passed onto our children, partners, friends and relations. The home becomes a prism of pain – of reflected trauma and shame. Unless another parent, extended family member or friend, witnesses and then takes appropriate action there’s no-one to shatter the glass cage. Extended family can often be aware of issues but feel powerless or are dismissed. Children need to be listened to and truly heard, in their words as well as their actions.

If there’s no one there to shatter the illusion or question the truth and actions of caregivers then the anger and shame felt is often internalised and/or acted out in harmful ways, to the self and/or others. This unrecognised pain can lead to adult addictions, the repetition of poor relationships based on that unhelpful dynamic and to behaviours such as fight, flight, freeze and fawn (e.g. workaholism, perfectionism, dissociative scrolling or media binging)

Mostly responsive, “good enough” parents and extended networks produce mostly secure children but almost all of us carry, and continue to use, the maladaptive strategies that we learnt as babies and young children. This is inevitable and, one might argue, a source of our human-ness. It can be the work of a lifetime to become aware of and undo these learnt responses and models. The behavioural grooves which early childhood carves in the brain are deep and well-worn and it take conscious effort, and time, to change tracks and take a different direction. It’s challenging but valuable work.

The trauma of a child who has been seen with disapproval and experienced a denial of its fundamental needs and feelings is a trauma that needs to be borne witness to, both within and without.

We need to be mirrored, to have our feelings and needs understood in those early years as often as possible so that we develop trust in ourselves and know how to interact in boundaried and respectful ways with others. To do this we need enough safety in ourselves, as well as within our relationships and personal space, to begin to feel and understand what we are experiencing and why. Feeling safe enough can create space to play, create and can provide access to the joy and pleasure, in body, mind and spirit, that is sorely needed. Relationships can create this (as my partner discovered through his relationship with my children) as can projects and other experiences of consensual and caring community. A trauma informed therapist can support this work as can a tool box of skills such as journalling, drawing, doodling, creating, dream-diarying and your-body appropriate movement.

And if, like me, you’re a person who has family and partners and who has only recently aware of the harm caused and created by your past experiences then, please, trust me when I say that you can and will feel better. Knowing the truth about your past will free your present and transform your future.

Recommended Reading

Recovery – Gravitz and Bowden

C-ptsd – Pete Walker

The Dance of Anger / The Dance of Intimacy– Harriet Lerner

The Truth will set you free – Alice Miller

Support

If you are looking for a private therapist, here are some links: London GSRD Practice and Pink Therapy

London Friend, the LGBT foundation, and Metro can help you find low cost therapy.

Anita Cassidy – me, the writer of this 🙂 – can support with creative coaching and relationship mentoring

If you’re in crisis, here are links to people who can help: